Mexican president-elect outlines oil sector rescue plans

Mexico’s incoming president has begun fleshing out his rescue plan for the country’s long-neglected oil sector.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s proposals include a $4bn capital injection for state oil company Pemex to boost exploration, a new refinery to slash reliance on US fuel imports and a 600,000 barrel-a-day increase in crude production in two years.

But analysts warn that his nationally focused energy policy risks putting unsustainable pressure on the world’s most indebted oil company. In particular, they point to plans for a 160bn peso ($8.6bn) refinery to be built in his home state of Tabasco over the next three years — an investment equal to the size of Pemex’s loss in the second quarter.

Mr López Obrador has not spelt out how he would fund his proposals but has named Octavio Romero Oropeza, a long-time confidante and agronomist from Tabasco, to take the helm of Pemex. “We are estimating overall investment to rescue the sector of 175bn pesos next year,” said the president-elect, who takes office on December 1.

The cash injection comes as Pemex has seen output fall from a peak of 3.4m barrels a day in 2004 to 1.866m in the second quarter this year.

Mr López Obrador said output was plunging because “the energy sector and oil industry were abandoned”, and has pledged to lift production to 2.5m b/d in two years.

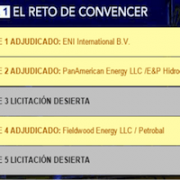

He has yet to make clear whether he intends to continue with oil tenders that have seen more than 100 contracts awarded to 73 companies since 2015 under a landmark reform designed to lift Mexico’s oil output from a four-decade low. The new administration wants at least a temporary pause to oil tenders.

“Four billion dollars is a significant amount, there’s no doubt. But it is important to put it in perspective . . . One single tender round can inject more investment,” said Pablo Zárate at think-tank Pulso Energético.

Mr López Obrador has promised to achieve energy self-sufficiency by spending 49bn pesos upgrading Pemex’s six lossmaking refineries, where output has halved since May 2013, and building two new ones to halt dependence on US gasoline imports, which have increased by a third in the past two years.

But investors are alarmed at the potential for snowballing costs. The price tag for the first new refinery, to be built in Dos Bocas, has already risen from the $6bn Mr López Obrador’s team had previously indicated. “I don’t know of a single refinery that’s ever been done to budget,” said an investor at a large fund who follows Pemex closely.

Pemex, a monopoly for eight decades, has spent the past two years putting its finances in order and making huge outlays on new refineries could be a serious risk, say analysts.

“Pemex today does not have the cash or free cash flow to take on the construction of new refineries, and if the company decided to finance such an investment with debt or shift capital from exploration and production to refining, its credit metrics would weaken,” cautioned Moody’s Investors Service.

Ramping up refinery capacity could lead to Pemex halving the value of lucrative oil exports, it added.

But Mr López Obrador has said his government would keep its promise of halting gasoline imports in three years and would lower fuel prices.

Pemex has net debt of about $106bn and is expected to post earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation of approximately $25bn this year. With the state taking about 70 per cent of profits in tax, Pemex could bump up its debt to pay for refineries — but it already has hefty debt repayments due in 2019 and 2020.

Mr López Obrador’s team has indicated that it wants to halt oil tenders while it reviews contracts awarded to date and decides on whether and how fast to continue auctions.

Indeed, the government has delayed two upcoming tenders, which include joint ventures with Pemex, until next February.

Adrián Lajous, a former Pemex chief executive, has called for a moratorium on oil auctions until 2020 but said joint ventures with Pemex should resume next year.

Even if oil tenders are put on ice, analysts are urging the new administration to allow Pemex to continue forging joint ventures.

“Partnerships will be needed to grow output — international companies bring capital and technical expertise,” said Ruaraidh Montgomery at Wood Mackenzie.

Above all “Pemex should start partnering with companies that specialise in enhanced oil recovery, given the maturity of its portfolio”, to allow it to squeeze more oil from existing fields, said Pablo Medina at Welligence Energy Analytics.

One radical revamp for Pemex could be to follow the “China model”, said Juan Carlos Zepeda, head of Mexico’s oil regulator, keeping the parent company in state hands, but spinning some assets into a partially listed unit, as China National Petroleum Corp has done.

“I would like us to do the same with Pemex but that would require changing the constitution,” he said.

This article has been amended to correct the amount of oil Pemex plans to increase production by in the next two years.

Financial Times / Jude Webber /